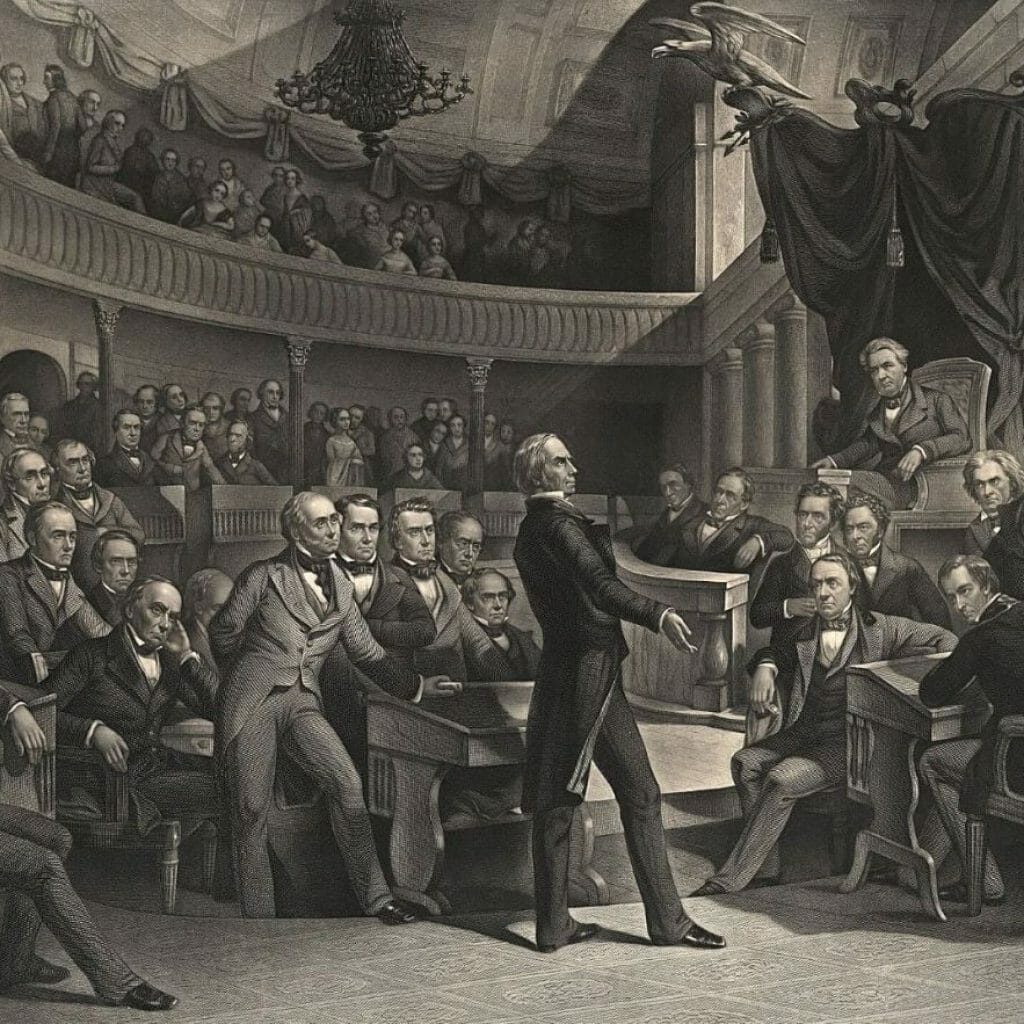

Henry Clay delivered a speech before Congress in 1824 in favor of the tariff to promote his economic approach which he termed, the American System. A representative from Kentucky and Speaker of the House at the time, Clay believed the tariff would provide protection for American industry. Below is an excerpt from the speech. His full remarks can be found here.

Having called the attention of the committee to the present adverse state of our country, and endeavored to point out the causes which have led to it; having shown that similar causes, wherever they exist in other countries, lead to the same adversity in their condition; and having shown that, wherever we find opposite causes prevailing, a high and animating state of national prosperity exists, the committee will agree with me in thinking that it is the solemn duty of government to apply a remedy to the evils which afflict our country, if it can apply one. Is there no remedy within the reach of the government? Are we doomed to behold our industry languish and decay, yet more and more? But there is a remedy, and that remedy consists in modifying our foreign policy, and in adopting a genuine American system. We must naturalize the arts in our country; and we must naturalize them by the only means which the wisdom of nations has yet discovered to be effectual ; by adequate protection against the otherwise overwhelming influence of foreigners. This is only to be accomplished by the establishment of a tariff, to the consideration of which I am now brought.

And what is this tariff? It seems to have been regarded as a sort of monster, huge and deformed—a wild beast, endowed with tremendous powers of destruction, about to be let loose among our people, if not to devour them, at least to consume their substance. But let us calm our passions, and deliberately survey this alarming, this terrific being. The sole object of the tariff is to tax the produce of foreign industry, with the view of promoting American industry. The tax is exclusively leveled at foreign industry. That is the avowed and the direct purpose of the tariff. If it subjects any part of American industry to burdens, that is an effect not intended, but is altogether incidental, and perfectly voluntary.

Mr. Chairman, our confederacy comprehends within its vast limits great diversity of interests: agricultural, planting, farming, commercial, navigating, fishing, manufacturing. No one of these interests is felt in the same degree and cherished with the same solicitude throughout all parts of the Union. Some of them are peculiar to particular sections of our common country. But all these great interests are confided to the protection of one Government—to the fate of one ship; and a most gallant ship it is, with a noble crew. If we prosper and are happy, protection must be extended to all; it is due to all. It is the great principle on which obedience is demanded from all.

If our essential interests cannot find protection from our own Government against the policy of foreign powers, where are they to get it? We did not unite for sacrifice, but for preservation.

The inquiry should be, in reference to the great interests of every section of the Union (I speak not of minute subdivisions), what would be done for those interests if that section stood alone and separated from the residue of the republic? If the promotion of those interests would not injuriously affect any other section, then everything should be done for them which would be done if it formed a distinct Government. If they come into absolute collision with the interests of another section, a reconciliation, if possible, should be attempted by mutual concession, so as to avoid a sacrifice of the prosperity of either to that of the other. In such a case all should not be done for one which would be done, if it were separated and independent, but something; and in devising the measure the good of each part and of the whole should be carefully consulted. This is the only mode by which we can preserve, in full vigor, the harmony of the whole Union.

The South entertains one opinion, and imagines that a modification of the existing policy of the country for the protection of American industry involves the ruin of the South. The North, the East, the West hold the opposite opinion, and feel and contemplate, in a longer adherence to the foreign policy as it now exists, their utter destruction. Is it true that the interests of these great sections of our country are irreconcilable with each other? Are we reduced to the sad and afflicting dilemma of determining which shall fall a victim to the prosperity of the other? Happily, I think, there is no such distressing alternative. If the North, the West, and the East formed an independent State, unassociated with the South, can there be a doubt that the restrictive system would be carried to the point of prohibition of every foreign fabric of which they produce the raw material, and which they could manufacture? Such would be their policy, if they stood alone; but they are fortunately connected with the South, which believes its interests to require a free admission of foreign manufactures.

Here, then, is a case for mutual concession, for fair compromise. The bill under consideration presents this compromise. It is a medium between the absolute exclusion and the unrestricted admission of the produce of foreign industry. It sacrifices the interest of neither section to that of the other; neither, it is true, gets all that it wants, nor is subject to all that it fears. But it has been said that the South obtains nothing in this compromise. ‘Does it lose anything?’ is the first question. I have endeavored to prove that it does not, by showing that a mere transfer is effected in the source of the supply of its consumption from Europe to America; and that the loss, whatever it may be, of the sale of its great staple in Europe is compensated by the new market created in America.

But does the South really gain nothing in this compromise? The consumption of the other sections, though somewhat restricted, is still left open by this bill, to foreign fabrics purchased by Southern staples. So far its operation is beneficial to the South, and prejudicial to the industry of the other sections, and that is the point of mutual concession. The South will also gain by the extended consumption of its great staple, produced by an increased capacity to consume it in consequence of the establishment of the home market. But the South cannot exert its industry and enterprise in the business of manufactures! Why not? The difficulties, if not exaggerated, are artificial, and may therefore be surmounted; But can the other sections embark in the planting occupations of the South? The obstructions which forbid them are natural, created by the immutable laws of God, and therefore unconquerable.